What are the symptoms of LVNC?

The symptoms people get can vary widely. Some people have life-threatening problems early in life, whereas others can have the condition their whole life and have no idea.

The heart’s difficult in pumping round the oxygenated blood can lead to breathlessness, fatigue, limited physical abilities, and swelling of the lower legs (oedema). Sometimes it can also affect the heart rhythm, making it fast or irregular. This can cause loss of consciousness or, in rare cases, sudden death.

What causes LVNC?

Specialists believe that LVNC is mainly a genetic condition caused by mutations, or alterations, in our genes. Your genes are like a blueprint for your body, and sometimes they contain slight errors or ‘mutations’. Because they’re part of your genetic makeup, you become what’s known as a ‘carrier’ and can pass them along to your children.

Gene mutations are passed down through families in many ways, but it is thought that every first-degree relative of a person with LVNC – a parent, sibling or child – has a chance of having the condition too and being completely unaware. It’s important that they see a cardiologist for screening, as early identification can have a huge impact on the condition’s future progression.

A number of genes have been associated with LVNC, but research is ongoing as the condition is not well understood yet. Genetic testing, which involves sending samples of blood or saliva to a lab for DNA testing, may be beneficial. At the moment we don’t know enough about LVNC to use DNA results to test for the gene, but it will help the research. Centralised registries are vital as they help achieve successful family screening programmes.

How is LVNC diagnosed?

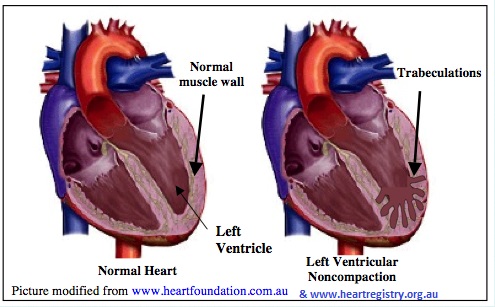

Diagnosis can be tricky, as a variety of conditions can cause the same symptoms. Echocardiography or MRI is used to look at the size of the trabeculations in comparison to the compacted muscle. This is a painless, non-invasive test that uses ultrasound to record different views of the heart, including its contraction and blood flow.

The features of LVNC can overlap with other heart muscle conditions such as dilated cardiomyopathy (where the heart is large and weak) or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (where part of the heart muscle has become too thick). This generally doesn’t affect your treatment plan, but it does make it hard to know exactly what is causing your heart’s problems.

How is LVNC treated?

Treatment will depend a lot on the individual patient and their specific range of symptoms. It may help to be prescribed medications to improve the heart’s pumping function, or to reduce the likelihood of dangerously fast heart rhythms. It’s important that you continue to take them and don’t suddenly stop, as this can increase the risk of symptoms.

People who are more severely affected might have their specialist recommend fitting an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), a device similar to a pacemaker that can also monitor heart rhythms and ‘shock’ the heart if it detects dangerous ones.

Your specialist will also recommend that you avoid strenuous activity, as this can suddenly and unexpectedly lead to a dangerous heart rhythm. You should also be regularly assessed by a cardiologist, as this is the only way to monitor the progression of LVNC.

It’s also important to know that a diagnosis of LVNC is likely to affect your insurance, and it may be harder to arrange it. LVNC is a recently identified condition, and many commercial insurers may struggle to understand it. They are more likely to be familiar with the term “cardiomyopathy”, though this is clinically a less specific description than LVNC. They may also ask for details from your GP or cardiologist, and this process can take quite a while.